Using a Platte Map to Research Ancestors

If you are not familiar with the concept of a platte map, you may be missing out on a valuable genealogy research tool. In genealogy, one of the main objectives is to gain a better understanding of the lives of our ancestors. By studying a platte map that includes our ancestor’s land, one can learn a surprising amount about the way they lived and interacted with their friends and neighbors.

Farming in America

In the United States during the late 1800s, a majority of the citizenry was engaged in the practice of farming. As a result of the Homestead Act of 1862, a large swath of the great plains was partitioned into 160 acre tracts which just about anyone could own outright if they met certain requirements living on the land and making improvements.

Needless to say, there was no lack of people willing to take the government up on their offer of free land. By 1880, there were 31 million Americans living on farms. If you had relatives living in the Midwest region of the country during this period, there is a good chance that they were farmers and possibly even an original homesteader.

Land ownership played a big part of a farmer’s life since working land is what allowed them to make a living. Keeping track of the ownership of land is where a platte map comes into play. A platte is a map drawn to scale that shows the ownership divisions of a piece of land.

Platte Map Example

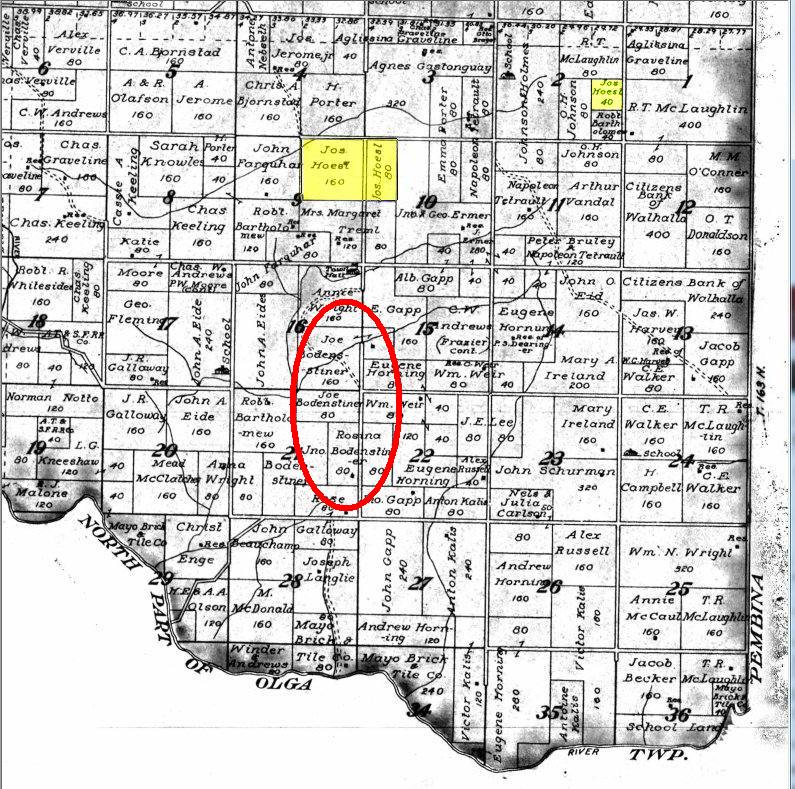

In order to illustrate the power of a platte map, I have included below a partial page of a North Dakota platte showing my ancestor, Joseph Hoesl’s homestead. Joseph submitted his homestead his claim paperwork in 1883, so this map from 1912 and shows the area as it existed 29 years after he first settled there.

The original government survey would have appeared as a uniform grid of 160 acre plots. Over the years, as land changed hands and was split into smaller pieces, land boundaries tended to take on a more irregular appearance. Below, I will describe the interesting observations that came to light as I analyzed the map and checked it against other pertinent documents.

First, we can see Joseph’s original 160 homestead claim, but also that he had purchased an additional 80 acre plot adjacent to it. An additional 40 acre plot was later purchased in order to grow hay to feed the livestock. As a wheat farmer, securing additional land would allow him to plant more acreage and increase his yield. The incremental expansion of his land holdings indicates a certain level of success in his farming endeavors.

Also, I found land owned by Rosina and Joseph Bodensteiner. Joseph’s mother’s maiden name was Bodensteiner and these were relatives of his mother. According to the 1900 US Federal Census, Rosina is listed as a widowed head of household and her oldest son Joseph (as well as five other brothers and sisters) all migrated in 1896 from a village back in Germany that was adjacent to the Bavarian village from which Joseph immigrated.

I also found them in the New York passenger lists originating from the German port of Bremen. It seems that Rosina’s husband immigrated with the family at age 53, but must have died before 1900, when the Census was taken. I can infer from these records that Joseph Hoesl was doing so well farming in America that his mother, back in Germany, enticed her family members to immigrate and homestead just as her son had. It is more than coincidence that later immigrating family members happened to end up in such close vicinity to each other (i.e. within walking distance just down the road).

On Joseph’s homestead paperwork, several witnesses were listed including Georg Treml and Otto Millie. If he felt comfortable enough to have these men vouch for him, it is likely that they were his close friends. On the map we can see Mrs. Margaret Treml owned the farm next door. It turns out that she is the widowed wife of Georg who died in 1906. I could not find any trace of Otto Millie in the records; he could have been a non-land owning farm hand who never showed up in a Census.

Conclusion

On the surface, the value of a platte map is limited to identifying exactly where your ancestor owned land. From the example above we can see the power of combining a platte map with existing documents and a little creative thinking to yield significant breakthroughs in understanding the actions of our ancestors.

It is important to take the time to study the map, closely examining

all the plots that surround your ancestor’s land. If you are lucky, clues to new facts will fall

into place which can be supported by documentation or further research. Sometimes the smallest thing, like a familiar

sounding surname or a witness listed in a document, will lead to an important new

discovery.

Read related articles: Record

Sources

Beginner

Guide

Genealogy Quick Start Guide for Beginners

Applying the Genealogy Proof Standard to your Research

Google Genealogy Research Toolbox

Find Records

Researching Ancestors through Military Records

Using the National Archives (NARA) for Genealogy Research

Using U.S. Census Records

Canadian Genealogy Research using the Internet

Tips

Genealogy Source Citations Made Easy

Listening to Genealogy Podcasts Made Easy